I’ve started a new blog at https://benexdict.io. It should be easier to follow because it includes an email newsletter that goes out with new posts, and I’m also experimenting with more personal content. I hope you’ll join me there!

Uncertainty and marriage

Deciding to get married was a mind-altering event for me. Some side-effects included confronting my mortality, dropping my religion, quitting my job, and publishing a comic book. Several friends have told me that my decision-making process was helpful to them, so I decided to write it up.

I met Amy in 2006 when we were both freshmen in college. Our relationship was a very slow burn, moving from an undefined kind-of-dating thing in that first year to a year of long distance after graduation, during which we enjoyed our almost-single lives in separate cities and spoke barely once or twice a week. Even when I first moved to New York to join her, we lived in separate boroughs for a year.

Because of how early our relationship started and because of the reality-distorting playground that New York represents for young adults, we were able to put off conversations about the future of our relationship for years. I don’t think marriage was even brought up until 2015, after nine years of dating. By then we’d fully merged our social circles and had drawers of things in each others’ apartments. Most of our friends had only ever known us as a couple. She eventually delivered the traditional message: it’s been fun, but now it’s time to make a decision.

worries and mental haze

This was a surprisingly difficult decision for me. I won’t go into the full timeline but it stretched over months and involved multiple outside counselors and a lot of hurt feelings. When I asked my friends and family for their thoughts, the advice was basically unanimous. Most memorably, a cousin told me, “I’ll support whatever you do, but you’re an idiot if you don’t marry her.” This was a pretty lonely time for me.

It’s obvious why other people gave me that advice. Amy is lovely, kind, generous, smart, and very cute. She has two doctorates and a great smile. One time when I was on a business trip and my dad was unexpectedly hospitalized, she spent a full day with him after pulling an all-nighter the night before to study for an exam. She was once spontaneously proposed to on the street. So what was wrong with me?

I had a few specific concerns. I think both Amy and I would individually be great partners to a lot of different people. We’re both even-tempered and easy to get along with, we have good professional careers but aren’t too obsessed with our jobs. We laugh easily and don’t escalate fights too often. But were we really specifically right for each other?

The details of my concerns don’t matter too much but I’ll go over them briefly. One mismatch is that I am much more novelty-seeking than her. Put less clinically, I feel like there is some kind of divine / creative spark behind our lives and I’m hungry to seek it out. There’s some feeling, like one day I’ll meet the right stranger or peek behind the right door and find a whole new world, behind the veil, that is suffused with light and meaning. I’m more interested in strange movies and scenes, weird art and weird artists. Amy prefers to watch the West Wing and the same three police procedurals on repeat. I get it! If I was working 10-hour hospital shifts every day I’d probably want to relax more too. But I’m not.

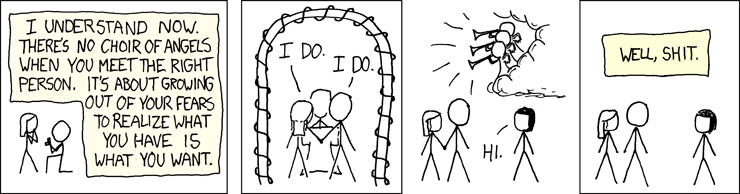

When I thought about our relationship, I didn’t feel the deep longing or the feeling of finally finding a missing piece that other people talk about. As silly as it is, this XKCD comic gave me serious mental stress during this time

Underneath it all was a lot of fear. What if I woke up one day in middle age and regretted spending my whole life with the wrong person? How was I supposed to know who the right person was? On the flip side, could I really walk away from such a great person over such vague misgivings? I looked for peace and reassurance but all I could find was more anxiety. I was paralyzed with indecision for months.

one day you will die

I know this is weird, but one truth that helped me finally make a decision was this: one day in the not-so-distant future, I was going to die. On that day, there wasn’t going to be a scoreboard or an instant replay to tell me whether I’d made the most optimal decisions throughout my life or show me how things would’ve gone if I had married someone else. There was just going to be my life, and how I felt about the choices I’d made. Would I be able to accept them?

Thinking about the end helped me in another way. The stakes felt so high because marriage is forever. How could I make a decision for forever? I’d never done anything like that before.

But I realized that actually, I was just making a decision for the next 70 years. And by putting off the decision for so long, I’d actually already made a decision for the last ten: to spend them with her. So I wasn’t trying to scale something up from 1 to infinity, I was trying to scale it up from 10 to 70. And by the way, I’d better learn to start making decisions consciously, because by putting off the decision, I ended up spending ten years in an undecided state. It’s not like I got to stay young forever by putting that decision off. Every day I was just getting older with an implicit decision instead of a consciously chosen one.

trust your instruments

Those realizations helped lower the stakes and helped me realize I really did have to choose. But I still didn’t feel anything, and no one had ever taught me how to make this decision or anything like it. I didn’t have any role models I wanted to follow. So how was I going to choose?

Sometimes I like to follow my wild impulses and see where they take me (see novelty-seeking, above). That’s led me into plenty of decisions that I won’t confess to in writing. But for the most consequential decisions, I try to be level-headed and just get the most important things right.

When new pilots get lost in the clouds, it’s easy for them to get disoriented and start to make bad decisions. The advice they’re given is: trust your instruments. When your senses are lost, they’ll tell you which way is up and which way is down.

The goal here was to find a partner that I could build a life with. The important criteria were the same ones they would be for anyone else: a partner who is kind, reliable, good at making decisions and resolving conflicts, someone that I was physically attracted to. I asked trusted people around me to double-check that I wasn’t missing any red flags. I might never know if this was going to be the best person for me, but I just had to make a decision that I thought would work out, and all of the signals were green. So I went for it. And she said yes!

postscript

As I mentioned above, the process of making this decision shook a lot of other things loose in my life. It’d been ten years of adulthood already! How long was I going to wait around in a job I didn’t love? How long was I going to put off creating the comic I wanted to write? Wait for some kind of sign from a God I was losing faith in?

Making decisions in the face of uncertainty is hard. I’d always been great at school, where careful analysis eventually yielded the fixed right answer. But learning to make this decision without a sure answer unlocked the rest of my life for me. Fingers crossed, but it’s been great.

Helping the helpers

Merry crawled on all fours like a dazed beast, and such a horror was on him that he was blind and sick. ‘King’s man! King’s man!’ his heart cried within him. But his will made no answer, and his body shook. He dared not open his eyes or look up.

Then out of the blackness in his mind he thought that he heard Dernhelm speaking; yet now the voice seemed strange, recalling some other voice that he had known. […] But the helm of her secrecy had fallen from her, and her bright hair, released from its bonds, gleamed with pale gold upon her shoulders. Her eyes grey as the sea were hard and fell, and yet tears were on her cheek. A sword was in her hand, and she raised her shield against the horror of her enemy’s eyes. Into Merry’s mind flashed the memory of the face that he saw at the riding from Dunharrow: the face of one that goes seeking death, having no hope.

Pity filled his heart and great wonder, and suddenly the slow-kindled courage of his race awoke. He clenched his hand. She should not die, so fair, so desperate! At least she should not die alone, unaided.

i

For as long as I can remember, my parents have been at the center of their church community. I was never sure if they would be home for dinner or if they’d be visiting someone sick or in jail, or helping with some church event. Both of them are still running the youth group and teaching Sunday School, more than a decade since my sister and I graduated. People still call at all hours to talk with my mom about their problems, to the point that she eventually went to get professional training for counseling. My dad helped run summer bible schools for kids in a poor Philadelphia neighborhood into his seventies. Out of a church of several hundred people, I’d guess that about a dozen people contribute at this level.

(For comparison, my mom just spent five months help to care for my sister’s newborn, and she now looks healthier and more well-rested than I can ever remember. As I understand it, this is a job that involves near-constant attention and not a lot of sleep. But she says that it’s quite relaxing to be able to focus on just one thing at a time.)

My Burning Man camp operates on a roughly similar model, scaled down an order of magnitude. The week-long burn is held on a dried-out playa with no plumbing or electricity, and camps are fully responsible for their own food, water, and shelter. So starting several months before the event, we start dividing up responsibilities – who is bringing food, arranging for water delivery, arriving early to prepare the campsite, staying late to make sure everything is packed away. But in practice there are about 5 people who end up shouldering most of the burden. I have a vivid memory of watching one friend try to pack up the entire camp by herself while everyone around her either tried to sleep off the previous night’s bender or rooted around for some way to keep it going. She knew that as the week ended, people would start to slip away in cars and buses, and only she would be left to make sure everything made it back in the trailer.

As another example, some campmates will cook meals for the camp ahead of time, but there’s only one couple who lugs the hundred-pound cooler full of those meals onto a plane and gets it to the playa, along with a U-Haul full of Costco supplies. They’ve had this responsibility for every camp year that I’m aware of.

I think of people like these as the Helpers, as in Mr. Rogers’ advice to “always look for the helpers”.

ii

I hate being one of the Helpers. I don’t know if it’s from carrying too many group projects in school or reading too much game theory, but I just can’t stand being part of a group where I’m putting in more than everyone else. I start feeling trapped, constantly looking around to see how much extra load I have to pick up from the people around me.

However, I find that I can work incredibly hard when I’m working alongside a helper. If there’s just one or two people who are bearing more responsibility than me, any lingering resentment is washed out by an incredible sense of sympathy for them and I find that I want to do everything I can to lighten their load. It’s also a lot easier for me to recruit others to help when I’m doing it on behalf of someone else. If it’s just me, I tend to think that it’ll be easier to just do it myself.

I think of the Helpers as the limiting factor for any community. To transform a network of transactional relationships into a community of deep reciprocal bonds, there just has to be a core group of people willing to put in more than they get out. They’re an invaluable bunch and it’s a tragedy whenever one of them burns out. So this sense of admiration and protectiveness quickly kicks in for me when I see them in action.

Three Personal Resources

Money isn’t everything – Don’t hire Bane

Six years ago I left a lucrative engineering job at Google to work for a startup, despite getting a few quick promotions there and a level of compensation that I have yet to reach again. At the time I didn’t have a framework to explain this decision to myself, let alone to anyone else. All I had was a feeling that something important was rotting.

There’s a movement called FIRE (financial independence, retire early) that presents this simple analysis of what you need to survive in the world. Take your yearly financial burn rate X and your present net worth Y. If you can generate more than X every year by investing Y, you have achieved Financial Independence. You can withdraw from the working world, safely insulated from the vicissitudes of fate.

This always seemed brittle to me. A job is also a source of interesting problems to work on and colleagues to collaborate with, a way to stay sharp and a call option on future work. What if a parent has an unexpectedly large medical expense, or some crisis forced us to flee the country and start over? If I had a lump of money and nothing else, would I have the flexibility to respond?

A great illustration of the money-only failure mode is this scene in The Dark Knight Returns. CEO Daggett has paid Bane a small fortune and demands to know why Bane hasn’t delivered Bruce Wayne’s company into his hands as agreed. He wants to remind Bane that Daggett is in charge.

Bane towers over him, calmly laying an open palm on his shoulder. “Do you feel in charge?” Bane asks. Daggett is shortly relieved of his misunderstanding (and his life).

If you think this only happens in the movies, take a look at Arm China going rogue.

Three Resources

Money is shorthand for your tradable resources. It’s the most flexible, the easiest to measure and to redeploy. Real estate, Pokemon cards, cryptocurrency, dollars stuffed in your mattress: with a bit of effort, any of these can be turned into another, or traded to someone else.

Besides money, there are two other resources to be aware of: your human capital, and personal network. Coming up short in either of these can be just as crippling as running out of money.

Human capital is your skills, your reputation and status, and your judgment. If you’re just starting your career, most of your net worth is in this bucket. This tends to be the most specialized and idiosyncratic of the three. People are “T-shaped” – very good in a few areas, adequate in a few more, often hopeless in others. That’s why you need the third resource, your network.

Personal network is the people you know and the people they know. There are two related concepts here. Friends and family are your community; they have reciprocal personal bonds with you. You help each other and cheer for each other to succeed. Along with this is a “web of trust”: people who don’t owe each other anything, but are known by each other to be reliable counterparties.

How to spend money

So what went wrong for Daggett? He did not have the personal judgment to know which hired gun to choose, and ended up backing a man who wanted more than money. He also didn’t have reliable connections among mercenaries that could give him referrals and assurances. In short, Daggett wasn’t a mercenary and didn’t know mercenaries, so he couldn’t hire them effectively.

Paul Graham calls this the design paradox. “You might think that you could make your products beautiful just by hiring a great designer to design them. But if you yourself don’t have good taste, how are you going to recognize a good designer?”

Still, the US Dollar is the ultimate tradable asset. We can convert it into the other two resources, if we are a bit more careful.

Converting money into human capital is relatively easy. Money buys you an education and hobbies; you can enroll in a class or hire tutors. The problem still exists – how do you recognize a good teacher if you’re unfamiliar with the field – but slowly you can bootstrap your way up. As you improve your skills, you can recognize better teachers. Money also gives you a safety net to experiment and fail while you learn.

Money can also buy you status, which is another part of your human capital. You can sponsor a social space for your community, or hire someone to take great pictures of you to post on Instagram. I think of wearing branded clothing as hiring an advertising firm to work for you part-time – after all, that’s what the brand association is doing for you. One friend suggests that “the ability to seem unquestionably upper middle class” is the most valuable form of status to have when interacting with bureaucracies or authority figures. All of this might seem a bit gross, but it’s worth being aware of the option.

Converting money directly into a personal network is a famously hard problem because of adverse selection. You don’t really want to be friends with people who only like you for your money. I’d recommend increasing your human capital first and then parlaying that into a better network.

Other conversions

Converting human capital into money is straightforward: get a job deploying your most valuable skill. The more interesting point is that these resources interact in a multiplicative way. If you have great skills but no one knows it, it’s harder to get a high-paying job. So the best path here is to grow out your network in parallel, so for the next job you have more options.

Nerdy intellectual types are often bitter when they learn the importance of a personal network. “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” is the common complaint – especially when trying to leverage either of those into more money. But really it’s both. You mostly meet high-quality people by increasing your own value first, and a large network won’t help you if no one in it thinks much of you.

Money is (as always) a self-multiplier as well. If you have a financial buffer to take more time to job search, you have a better chance of finding something great. I recommend taking a few months off to dedicate to searching if you can afford it. The difference between a good job and a bad one is quite large. This is especially true in power-law dominated fields like startups.

Life after Google

Looking back, it’s clear to me that it was my subconscious accounting of my deteriorating network and skills that drove me out of Google. This isn’t true for everyone; certainly I have friends who have gotten a lot of personal growth and valuable connections during their time there. But it was true for me. I wasn’t working very hard, especially near the end, and my knowledge was heavily Google-centric. My professional network was weak outside of Google because no one ever left, because the money was too good.

I struggled for a while after leaving. I was missing important skills, both in technology and also in personal time management. I didn’t know how to find a good startup because I didn’t know yet who to talk to or what questions to ask. (Too long to get into here, but in short: team, unit economics, and customer acquisition costs.) This is brutal in startups because almost all of the value is created by the top 1%, so if you don’t have a way of improving your targeting you are overwhelmingly likely to be wasting your time.

What I did have was a lot of financial runway and a lot of “brand recognition” to trade on from my background and time at Google. Slowly I was able to figure out what was going wrong and patch up some broken mental models and habits.

One particularly useful form of shock therapy was starting my own startup. Needing to find customers forced me to reach out to other people and understand what they needed – the basis of any network. On the technical side, I had to do everything that I would’ve passed off to a more knowledgeable coworker in the past, from API documentation to standing up servers and setting up monitoring. Although the startup didn’t work out, a VC we worked with was able to connect me to the very promising healthtech startup that I’m at today.

Google has done very well since I left and it’s hard not to think about the opportunity cost of the salary and RSUs that I left behind. But I feel much better balanced with resources that I can count on besides just money.

The world is very weird of late and I expect it to keep getting weirder. When thrown into a new situation I try to take stock of all three of these resources and work out how to bring them all to bear. Any one alone can come up short, but together they are very powerful.

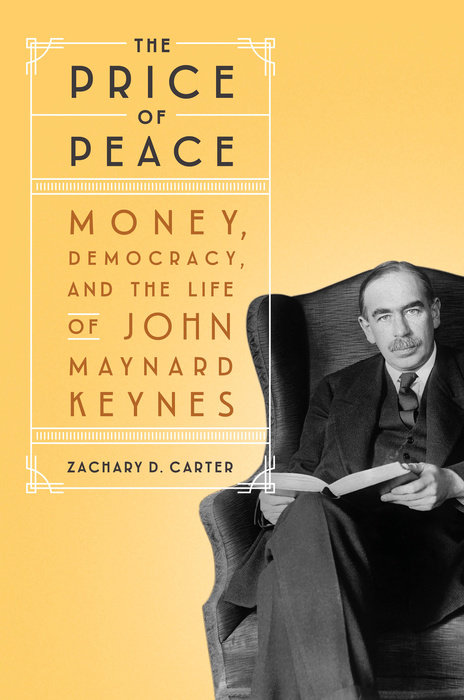

Review of "The Price of Peace"

I recently finished reading The Price of Peace, Zach Carter’s biography of John Maynard Keynes. I had a basic sense of what Keynes advocated for economically (more government stimulus!), but I had no idea about how his life influenced his theories or vice versa. I mostly pictured him as an lonely academic coming up with theories in his ivory tower. I enjoyed learning that I was wrong on both of those counts.

Bloomsbury

The first interesting thing this biography describes about Keynes is his choice of friends. Keynes hung out with a group of cosmopolitan sexually adventurous artists and writers which included Virginia Woolf, her sister Vanessa, and many other people with Wikipedia entries, some of whom I’m sure I would recognize if I knew anything about art or literary history. They called themselves “the Bloomsbury Set”, which sounds unbearably pretentious now and probably also did at the time. In my personal life I’m very fond of people like this, so these sections were equal parts enjoyable and frustrating to read for me.

Here are some excerpts to give you the flavor of the group:

His social engagements were typically organized around highbrow debates over aesthetics, conversations among friends who swapped lovers and opened their marriages, insisting to others in their tight community that such romantic chaos was itself an act of social progress.

But for all their sexual and intellectual fecundity, the members of this whirlwind collective had accomplished very little as they approached middle age. One of Maynard’s closest friends, Virginia Woolf, fancied herself a writer but had never published a book.

“I have always suffered and I suppose I always will from a most unalterable obsession that I am so physically repulsive that I’ve no business to hurl my body on anyone else’s,” Keynes wrote. It was a common sentiment among the group; Virginia Woolf once noted the lack of “physical splendour” and even “shabbiness” among the Apostles, one of whom she eventually married. But Keynes always knew the Apostles admired his intellect, and that awareness emboldened his sexual confidence.

The war exploded everything. The parties, the ideas, the code of ethics were revealed to be, in Virginia’s words, so much “lustre and illusion.” In all their conversations about sex and truth, Bloomsbury had never really confronted questions of power, violence, or imperialism. “How could we be interested in such matters,” Vanessa wrote, “when beauty was springing up under one’s feet so vividly?”

Keynes stuck out in this group because he was an academic and a government functionary, not an artist. There is one funny story about how he tries to win back the favor of the group after engaging in the decidedly un-artistic work of negotiating settlements between the US and England during World War I. Because his duties took him close to the front in Paris, Keynes was close at hand when Degas passed away and his studio auctioned off a number of paintings. Keynes was able to persuade the Treasury to bankroll his purchase of several paintings, including a still life by Cezanne. I’ll let Virginia Woolf fill in the Bloomsbury reaction here:

“Roger very nearly lost his senses,” Virginia wrote. “I’ve never seen such a sight of intoxication. He was like a bee on a sunflower.”

Carter draws a line from Bloomsbury to Keynes’s larger political and economic philosophy. Bloomsbury represented “the good life”, the purpose of human civilization and progress. Militarism and war were threats to this good life. A well-ordered economy would prevent those threats from growing.

Two more anecedotes about Keynes’s personal life: he was friends with the Viennese philosopher Wittgenstein, who was studying at Cambridge before World War I but returned home to fight for the Central Powers. During the war they corresponded across battle lines to discuss Bertrand Russell’s work on logic and Keynes’s on probability. It always surprises me how tightly clustered some of these influential people are.

Keynes also married a Russian ballerina named Lydia early on in his career, despite mostly being interested in men up to that point. She writes him a number of enthusiastic letters about how famous and influential he is becoming. Bloomsbury was predictably snotty about this relationship. Here is Virginia one last time:

“Lydia came over here the other day and said ‘Please Leonard tell me about Mr Ramsay Macdonald. I am seerious—very serious.’ However then she caught a frog and put it in an apple tree; and that’s whats so enchanting about her; but can one go through life catching frogs? … I assure you it’s tragic to see her sitting down to King Lear. Nobody can take her seriously: every nice young man kisses her. Then she flies into a rage and says she is like Vanessa, like Virginia, like Alix Sargent Florence, or Ka Cox—a seerious wooman.”

That’s not very nice of you, Virginia.

Career

I also had no idea how involved Keynes was in the events of his day. As I said earlier, I assumed he was an academic who was mainly influential through his theories. Quite to the contrary though, he had governmental positions where he worked on issues as varied as: bank runs on gold-backed notes, the Treaty of Versailles and German reparations, advice to FDR on ending the Great Depression, and negotiations on the formation of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund at Bretton Woods after the end of World War II.

I think Carter’s bias bleeds through in these descriptions and it’s hard for me to evaluate the exact truth behind his narrative. In many of these scenarios, Carter presents Keynes as influential but ultimately overruled by other stakeholders, later to be proven correct by later events. Of course this counterfactual is difficult to really evaluate. I’ll go through them in order briefly, giving only the view as presented in the book.

During the bank runs, both foreign and domestic holders of British notes lost confidence in the banks, and tried to redeem the notes for gold. Domestic bankers advocated for England to keep its gold at home to shore up the banks. Keynes pushed for the opposite: foreigners should be paid in full in gold, and domestic holders given a new paper currency. Keynes won out in this debate, Britain’s foreign credit and reputation was left intact, and the banks were stabilized. Keynes broke the illusion of the market as all-knowing and self-balancing. Instead bankers were shown to be panicky and only looking out for themselves.

On the German reparations post-WWI, Keynes thought there was no way the Germans would be willing to live up to the terms imposed on them and despaired about the punitive treaty. He writes:

“The existence of the great war debts is a menace to financial stability everywhere. There is no European country in which [debt] repudiation may not soon become an important political issue. Will the discontented peoples of Europe be willing for a generation to come to so order their lives that an appreciable part of their daily produce may be available to meet a foreign payment? I do not believe that any of these tributes will continue to be paid.”

Of course, history proved him right on this point.

Keynes wrote his magnum opus, “The General Theory of Employment”, during the Great Depression, arguing that the economy was mainly driven by demand and not by supply, and thus the government could induce a recovery by spending more on infrastructure. He corresponded with FDR but it’s unclear how much influence he really had. Regardless, mainstream belief is that government spending really did break the Great Depression, proving Keynes right yet again.

One funny aside here that Carter makes here: “The General Theory of Employment” is esoteric enough that many economists have made their careers by purporting to explain it, including several schisms in pro-Keynesian schools.

Finally, Keynes was dispatched to Bretton Woods after World War II to negotiate the structure of international financial governance after the war. His vision was to produce a strong governing agency that would prevent any country from running up either trade surpluses or deficits above a certain size. In his view, countries exporting more than they imported were actually acting selfishly and harming the economies of their partners. They were preying on the countries running deficits by sucking up an extra share of demand. (Remember, in his view, demand is what is important for modern economies, not supply). However, he was overruled by the more conservative American vision, which instead created the modern World Bank and IMF.

I thought that this analysis of global trade was particularly interesting given the recent negotiations between debtors like Greece and creditors like Germany. It sounds like Keynes would disagree with the moralistic view of Greece as “consuming more than they deserved.” Instead he might say that their local economy was starved of demand and would advocate for policies leading to more balanced local production and consumption, perhaps even including some tariffs and protectionism.

The book concluded with several chapters on how Keynes’s theory was interpreted and how it ultimately fell out of favor in America due to anti-socialist sentiment during the Cold War. I mostly skipped these parts, although it was interesting to learn that Hayek (pro-austerity, anti-intervention) was a friendly colleague to Keynes but substantially less influential during their lifetimes.

Review

I enjoyed reading the Price of Peace. I found the narrative very agreeable, in both of the parts that I’ve highlighed – Bloomsbury because I found them very recognizable in my social groups, and Keynes’s economic work because I admire practitioners (vs theoreticians) and because I tend to agree with his views. I did feel a little suspcious of how smoothly everything lined up, but I suppose that sanding down the edges and crafting a neat narrative is part of creating any biography.

Church and Community

I recently left Manhattan after 10 years of living there. As a New Yorker, I found that I really needed a pipeline of new friends to replace the ones that were constantly moving away. In the time I was there, I had three full rotations of close friends come and leave, and I sometimes felt pretty depressed at the prospect of needing to go and replace them yet again. This June it was finally our turn to go. As we’re getting older and thinking of starting a family, it seems like a good time to think about what we want next.

In our twenties, our social groups didn’t have much to ask of each other besides providing some company. Some people were good for parties and clubbing because of their high energy and attractive friends. Some were drinking buddies because they were smooth conversationalists and knew the bartenders. I went rock climbing with some, wrote a graphic novel with one, went on ski trips and attended nerdy meetups with others. Sometimes if a friend was having a hard time, we’d talk about it over dinner or a few beers, but not too often.

I sometimes thought about the contrasts with the church that I grew up in. That was a much tighter community, where people came and went less often, and had their noses in each other’s lives much more. My parents are still part of that church thirty-some years after its founding. I don’t know which model of social connection is better, but I thought it’d be interesting to do the comparison.

Things that I miss about church

The thing I most remember about church is that there were always people around to help. If my mom was busy, one of her friends picked me up from school and hosted me for a few hours until my parents fetched me. People came by with cooked meals if someone was sick, or with groceries if they happened to buy extra. We swam in other people’s pools, borrowed their power tools, watched their DVDs.

My parents returned the favors, of course. They spent hours counseling people on the phone or in person, visiting people in prison, teaching Sunday School and bible studies, and hosting graduation parties and prayer meetings. There are friends I’ve lost touch with who will still call my parents for advice. A lot of older adults struggle with a sense of purpose after retirement, so I’m grateful that my parents are still able to contribute to their community.

Church also gave me some outlets for emotional expression – not the healthiest ones, but still some badly-needed outlets in an otherwise stoic Asian immigrant upbringing. People got up to give testimonies and confessions on Sundays, or had emotional epiphanies at week-long retreats, and then we cried and celebrated together. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen my father cry over anything personal in my life, but I’ve seen the waterworks come on for some hard-hitting sermons. Like I said, maybe not the healthiest, but better than nothing.

One thing I didn’t appreciate until much later is that everyone mattered in church. My parents spent many hours with a convicted murderer and with wildly mentally ill members of our congregation. Meetings were open to anyone who cared enough to show up consistently, and nonbelievers were eagerly welcomed in. I’m sorry to say that this sense of egalitarianism did not extend far among us kids, and we enforced our pecking order more viciously than any secular group I’ve been part of since. Still, I remember the times that an adult took me aside and asked me to include some awkward newcomer in our group, or told me that I’d really hurt someone’s feelings. It took a long time, but the lessons eventually sunk in.

Things I hated about church

Church is really stifling. I don’t just mean that the sermons were boring, although they often were. But the range of acceptable beliefs and actions was just very narrow. This annoys me in two ways. The first is that weird people are interesting, and pushing the boundaries is fun. I grew up feeling like I was missing out on a lot of fun. I thought maybe it would turn out that the adults were right and I’d be happy I listened to them. But I’m older now, I’ve tried most of the things I was warned against in church, and I really feel none the worse for wear.

The second problem is that it makes it hard to be honest. In church we valued having deep, personal conversations with each other, but it felt like people always held something back. Whether it was something about the sermon that didn’t make sense or some sexual experience you’d had, there were a lot of things that were repressed for fear of judgment. Sometimes these things surfaced, but only in a context that expected confession and repentance. Not much room for open and neutral conversation.

A church community is also necessarily limited. I don’t think my parents had many friends who really “got” them. Their friends believed the same things as them and cared about each other, but the community wasn’t big enough to always find people who had matching personalities or similar styles of communication and friendship. There’s some kind of loneliness in that.

What makes it work?

Church was a big time commitment for us. We had prayer meetings on Tuesday night, Friday night youth group, Sunday services and Sunday school, and then Bible study later at night. I can’t put this squarely in either column, good or bad. It seems like commitment is at the root of both. It’s easier to trust a group of people if you know that you are all committed to the same things. But those same expectations can feel very constraining.

Interestingly, though church demanded a lot of time week-to-week and a lot of commitment in terms of belief and lifestyle, it didn’t ask for the kind of commitment that would’ve solved my friendship issues in New York: the commitment to stick around long-term. A few people did move away, mostly for better jobs in other cities. Still it was a pretty rare thing. I’m not sure if that’s because people were older and more settled, or if the community was important enough that people naturally chose to stick around. I know I’d worry about my parents if they left.

It seems like some form of commitment is important for a community. Some of it probably needs to be explicitly agreed to, and some of it is just the slow building of reciprocal and implicit bonds between people.

Does commitment need to feel so limiting, though? I don’t think I have an answer to that, at least not yet.

Fixing healthcare incentives

(This post is about my day job, written at my own discretion. All opinions are my own only.)

About twenty years ago, my father had his life saved by a bowel movement and a bad guess. He noticed some blood in the toilet and thought that it might be a sign of something worse, so he made an appointment to see his doctor. On examination, it turned out that the blood came from an ordinary hemorrhoid, the kind most adults get from time to time. Blood in the stool is common enough that absent other risk factors, a doctor will usually just tell the patient to ignore it.

On his way out the door, my father’s primary care doctor mentioned that they could refer him out for a colonoscopy if he really wanted, even though it wasn’t necessary. But my dad went for it, and during the procedure the gastrointestinal (GI) specialist found an unrelated cancerous polyp. Because the cancer was found so early, my father’s treatment was short and successful, instead of the 15% survival rate he would’ve faced had it been caught later. All because of a lucky hemorrhoid.

How can we systematize this early screening and reduce America’s dependence on well-timed hemorrhoids? First, you’d want to gather some statistics and do a cost-benefit analysis based on who is most at risk, with enough years of life remaining to benefit from early intervention.

It turns out that the optimal policy is that adults from 50-75 years of age should get a colonoscopy every ten years. But armed with that knowledge, we find that we’ve only barely scratched the surface of the problem.

1

Now we face the challenge of rolling this policy out to the 93 million Americans who meet the criteria for this screening. They are cared for by roughly 70,000 primary care physicians, who belong to a truly bewildering variety of hospital systems, insurance networks, and independent medical practices. There is no reporting chain that includes all of these doctors, and therefore no one in charge to give the order.

Perhaps the closest person we will find is Seema Verma, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), confirmed by the US Senate in 2017. None of these doctors report to anyone who reports to her, but she does set the policies and reimbursement plans for Medicare. Medicare is the federal healthcare insurance program covering 65-and-older Americans, which means that Medicare pays the institutions that pay these doctors.

Suppose you have the ear of Ms. Verma. What would you suggest?

CMS could run some PSAs on the benefits of colonoscopies, but the track record for governmental public health campaigns is not encouraging. A rectal probe every ten years is a lot to push for in a 30-second TV spot. People trust their personal doctors, not talking heads on the airwaves.

Perhaps Ms. Verma should tell doctors to push their patients to get colonoscopies. But remember: none of these docs report to the CMS administrator. Medicare signs the checks that their practices cash, but those checks are written out for specific procedures that the doctors are billing for, not for following top-down orders. Plus, the primary care physicians (PCPs) that have longterm relationships with these patients are not the GI docs who perform and get paid for the colonoscopies. Get a colonoscopy, and your PCP doesn’t see a dime of that reimbursement. Skip the colonoscopy, and it’s the cancer surgeon, anesthesiologist, and hospital night-shift nurses that are getting paid instead when you need life-saving surgery ten years later.

2

Why this emphasis on money, anyways? After all, patient health is the goal and money should be a distant second. I think that is certainly true for the doctors I know, who are intrinsically motivated to keep their patients healthy and well. That’s why many of them became doctors, and most will go above and beyond for their patients without a second thought.

Still, on the margin, the external incentives do matter. A primary care practice is in many regards a small business, with rent and employees to pay and a very limited number of hours in the day. There is always more work to do, and a directive from a far-off federal administrator is not likely to get a lot of attention if it isn’t associated with any concrete up- or downsides. The closer we can align the practice’s financial incentives with their altruistic ones, the better off everyone will be.

One of the biggest misalignments in our system is the “fee for service” model. This means that practices are paid per procedure they perform. An annual care visit is $100. A colonoscopy is $3,000. Colon surgery costs $30,000, plus a few thousand dollars per night in the hospital. (Prices are approximate, split between patient and insurer, and vary wildly – a topic for another time.)

This means that healthcare clinics are paid more when a patient has more procedures. Completely different medical practices would be performing and charging for an annual care visit, a colonoscopy, or a cancer operation. This usually isn’t any kind of direct payment to the doctor, but you can be sure that some hospital administrator is keeping an eye on how these high-reimbursement procedures are growing year-over-year and what is driving their growth.

Various attempts to fix this misalignment have been underway for more than a decade, under the general umbrella of “value-based care”. Value-based care broadly means that a healthcare system should be rewarded for keeping its patients healthy, not for the number and complexity of procedures its patients get. Value-based care is something that Ms. Verma and her predecessors care about a lot. It’s probably the only way to keep Medicare from collapsing under its growing costs (to say nothing of expanding it to the whole population).

Two of the biggest levers in value-based care today are Medicare Advantage (MA) plans and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). A Medicare Advantage plan is an insurance plan offered by a private insurer like United Healthcare or Aetna, run for the benefit of Medicare-eligible patients and paid for by CMS. About a third of Medicare-eligible patients choose MA plans for a variety of different reasons including network coverage, pharmacy plans, or lower costs. CMS compensates these plans a baseline of $10,000 per patient insured per year, more for sicker patients.

This arrangement has some very attractive features from a value-based standpoint and for our nascent pro-colonoscopy campaign. The insurer receives a fixed amount that does not change based on how many medical procedures a patient receives. A patient will hopefully stick with this plan for many years, so preventative care this year means a healthier patient next year and fewer expensive procedures in the future.

An ACO is a similar value-based approach for a group of doctors instead of for an insurance plan. Same deal here: healthier patients and more preventative care equals better business for an ACO, again paid by CMS.

A final important feature of these organizations is that CMS cuts their checks and dictates their terms directly. Did we say $10,000 per patient? We can do a bit better than that, if your MA plan hits a certain target percentage of patients getting those colonoscopies. And if they fall below a certain lower threshold? Well… those were some nice reimbursements that we paid out last year. It’d be a shame if anything happened to them this year.

At last, we’ve found a receptive audience for our colonoscopy messaging. More probes! Less cancer! More preventative care! Fewer surgeries!

3

So here is a corner of the medical system that seems likely to respond to our colonoscopy cheerleading. In the real world, the folks at CMS got here way ahead of us, and are already offering big bonuses to ACOs and MA plans for meeting their targets for colorectal cancer screenings. So what’s left to do?

The devil still lies in the details. Sure, a doctor belongs to an ACO, which theoretically gets paid more by CMS if more patients get screened for colorectal cancer. But that’s assessed once a year, across the whole ACO, which is a collective of hundreds of doctors. So if you do your part but the other docs don’t, no one is seeing any of those extra value-based rewards. And even if everyone hits the threshold, the checks don’t arrive until the next year. Even when the checks arrive, they probably aren’t going to the assistants who are actually calling patients for screenings. Not a very effective feedback loop for motivating behavioral change.

For a Medicare Advantage plan, the problem is even worse. The relationship between doctors and insurers can be strained, when claims are rejected and requests for data are ignored. If I’m a doctor, why should I care if your insurance plan is hitting their screening goals for the year? This patient came in with a sore throat and I have to remember to talk to him about getting his butt probed by a different specialist at a different practice? I don’t even get to bill for that!

We’ve finally arrived at the last missing link, the piece that we’ve been working on for the last three years. Recap: CMS is the ultimate bag-holder, the organization charged with keeping all of its patients healthy and the one that gets hit with massive bills if they get sick. CMS is willing to pay extra to risk-sharing ACOs and MA plans if their patients get screenings for early treatments. The last step is to get those incentives to the doctors and medical assistants who can actually talk to patients about the screenings.

So that’s what we are working on now. Our platform identifies eligible patients, and actually pays doctors and medical assistants upfront for making sure that these screenings get done. That software is provided free to the medical providers, and all of it is paid for by the ACOs and MA plans that are eager to spend some money today to make sure their patients are hitting those screening thresholds this year. We do this for colorectal cancer screenings and about a dozen other measures around preventative healthcare and medication adherence. (Our biggest win recently has been helping quarantined patients get their prescription meds through the mail.)

It’s worth drilling into the costs again. For a patient, colorectal cancer surgery is a painful procedure with a long and uncertain recovery. For CMS, it’s $30,000 and a sicker patient to insure in the future. For the ACOs and MA plans, it’s a mark against their orgs and lower reimbursements from CMS.

But if we can convince an overworked medical assistant to stay an extra five minutes to call and convince their patient to go get that early screening, all of that can be avoided. It’s a huge win for everyone if we can pay that assistant an extra $20 to make sure that gets done, especially if we have the software in place to make sure exactly the right patients are getting that call.

Value-based healthcare is all about finding the tiny moments that make the difference. It’s not always glamorous. No CPR on flatlining patients, no flashes of diagnostic genius or heroic last-minute surgeries. It’s routine things like checking glucose levels and making sure patients are getting their prescriptions filled and their screenings on time, keeping them healthy instead of pulling them back from the brink. Our doctors and medical staff do that better when our software makes it easier and more rewarding to do.

My dad had a lucky hemorrhoid that saved his life. We can make sure that no one else has to count on that. If you’d like to work towards that, please get in touch with me! (Jobs link if you’d rather not go through me).

The self is a leaky abstraction

A few illustrations of the fragmented self.

Most of my enjoyment of a bag of chips comes in the first few bites, and most of the regret comes in the last few. So the obvious thing to do is to open the bag, take a few bites, then close it back up.

When I start to think about doing this, something weird happens. I move the bag closer to my face, my hands pluck out the chips more rapidly, and I actually speed up my eating for a few seconds before I’m able to overcome this impulse and close the bag. It’s as though there’s a part of myself that knows the treats are about to disappear, objects vehemently, and begins to fight back.

The abstract of a Nature Neuroscience paper (Soon, 2008):

There has been a long controversy as to whether subjectively 'free' decisions are determined by brain activity ahead of time. We found that the outcome of a decision can be encoded in brain activity of prefrontal and parietal cortex up to 10 seconds before it enters awareness.

St. Paul, much earlier and rather more dramatically:

I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want to do, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it.

And finally, an AskReddit post titled: “If your future self was trying to murder you, would you resist?”

“I'd fight like hell,” says user rhedrum. “I'm constantly sticking it to future self anyway, why would I take any of his shit if he came to kill me. On the other hand, I would take past self out if I had the chance to go back in time. He has done nothing but screw me over and its about time he paid for it.”

Whether you find these examples funny, frightening, or just a bit weird, you can probably see the common thread that runs through them. Your self is not a coherent whole, pursuing a set of goals continuously throughout time. You fight yourself, forget yourself, change without warning.

But what’s the alternative? It seems so useful to think of selves and people and personalities. How do you even make sense of the world if you don’t exist? The Buddhists say that the self is an illusion, but it’s hard to imagine what you ought to see in its place.

So I’d like to propose a different position. The self is not an illusion, but a leaky abstraction.

what is an abstraction?

Imagine a simple four-function calculator. Cheap plastic, about 15 buttons on the front. You press 1 + 3 =. What do you expect to see? How do you make that prediction?

Perhaps you pictured some little black cells on a pale green backdrop, four in total making the shape of a rudimentary 4. To get there, you did some arithmetic. The whole thing took you less than a second.

Someone with a detail-oriented view of the world and an obsession with electronics could take quite a bit longer. They might think, when I press the 1 key that compresses a rubber membrane and causes a bit of copper to fall into place to complete a printed circuit. This changes the voltage running to one port on the processor, which has a series of logic gates and capacitors that work to store inputs and simulate arithmetic. And a similarly complicated process translates the processor signals back into the liquid crystal display.

You could drill down even further. Electrons move through the copper wires in nondeterministic ways, which are described by certain patterns in quantum mechanical equations…

This is the wrong level of abstraction to answer the question. Missing the forest for the trees, as the saying goes. But it depends! If someone asks you the height of the tallest tree, you have to pop back down a level to see the trees again.

When I ask what you see when you input 1 + 3 into a calculator, the right abstraction for the calculator is something like “this thing does arithmetic, then displays the result on a little green screen.”

So an abstraction is a mental shortcut, an ellison of unnecessary details which helps you reason about the world more effectively.

what is a leaky abstraction?

Suppose you input 1 + 3 =, and the screen shows you a 1. Suddenly you realize that there’s some flaw in your idea that this thing does arithmetic and shows you the right answer. How do you figure out what’s going wrong?

Perhaps the + or 3 buttons are broken. Or maybe it’s low on batteries and that’s causing some kind of problem. Maybe part of the display is broken, so the extra cells that are required to display the 4 aren’t showing up, even though it’s doing the math correctly.

A little part of you wonders, what does it even mean for a calculator to do math? How does that work, anyways?

This is called a leaky abstraction. One of the details beneath the surface, something you abstracted away, is popping its little head back up again. Your model was so useful before, but now you have to remember that there were layers underneath it.

the self is a leaky abstraction

At the beginning of this post, I poked some holes in the idea of the self. The self is fragmented, not unified. Mutable, not constant. There’s plenty of holes there, enough for serious edge cases to slip by. Is it fair to punish people for what they do when they are “not themselves”, overcome by rage or drunkenness or mental degeneration? Should we continue to hold a reformed adult responsible for something that a child did decades ago, just because they share the same body and memories?

What good is this abstraction doing, anyways? Isn’t the self an illusion, a construct dividing the islands of our universal consciousness? Just a piece of wool pulled over our eyes by an evil demiurge?

I don’t think so. The self is an abstraction, but a useful one. I have memories of the things that past-self did, both good and bad. I can learn from the actions of my past selves in a much more visceral way than I can learn from the stories of other people. Future rewards and punishments can shape my present behavior. I’m not completely the same every day, but I stay similar enough to be comprehensible to other people and even loved and trusted by some.

Different pieces of me want different things, but they can work together towards mutual satisfaction. The point of putting away the bag of chips is not to deprive my inner glutton, but to give it more enjoyment given the same costs, and to balance the needs of the glutton-fragment with the other self-shards that want to look good and feel good.

We should try to see the abstraction of self for what it is: a useful tool. Sometimes I need to look beneath the surface, to see why I am at war with myself. At those times I think it’s better to see myself as an abstraction on top of disagreeing fragments, not as a soul possessed by unreasoning sin. Sometimes I need to abstract above myself – not just a self, but part of a group that cares about all of its members.

The self can be an abstraction that helps us guide the pieces that make up the whole. Fragmented, but not shattered. Leaky, but still holding together.

Faithfulness

Doubt is a cherished state of mind for most intellectuals. “Thinking critically” is the first thing we’re taught in school, and the ability to question and update our assumptions is what elevates us above the less enlightened. We think that unexamined belief is easy and doubting things is worthwhile and hard. When we think of faith, if we think of it all, we think of outdated religious claims that haven’t been subjected to enough skepticism.

When in doubt, you might say, add more doubt.

But is this the right model? There’s an alternative meaning of faith that is quite useful, that survives in phrases like “being faithful to your spouse”. Roughly speaking, this means keeping the promises that you make, even after a long time has passed, even when you don’t feel like it.

I think this is more than a historical coincidence. While it’s true that we don’t often seek out new evidence to change our minds, we do change our minds and our behavior all the time, regardless. Often this happens without any evidence or reasoning process at all. As each day passes, we just feel a little less conviction about our commitments. Is going to the gym today really that important? Will another cigarette really make any difference? Perhaps what we need is just a bit more critical thinking about your original premises?

No! Nothing relevant has changed since you first made that commitment. Except that the strength of your conviction fades day by day with no external input at all, just as it does for everyone else. So faith is the ability to fight that constant, unreasoning doubt that otherwise nibbles everything away. It is the practice of keeping your commitments, both to the belief and to the action.

1

Here are some examples of propositions where it’s useful and difficult to “keep the faith”.

- Regular exercise will improve my health, mood, and appearance.

- This startup will definitely succeed, as long as we work hard and don’t give up.

- My co-conspirator and I commited to cooperating, we will not defect against each other.

- If I keep talking to girls, some of them will like me.

- If I hang onto my investments through this downturn, stocks will recover and tend to appreciate over time.

- If I keep on writing, my writing will improve.

Of course, any of them may or may not be true, depending on the situation. But suppose you’ve convinced yourself (even provisionally) that such a proposition is true, and committed yourself to act accordingly.

One thing that these things all have in common is that we need to make a decision before we can see the outcome. Most of the time, we will have to stay faithful to that decision and continue to act on it for some time before we see any results. At some point we will find ourselves asking whether the process is really working.

It’s a fine question to ask. But often it’s just a standin for the statement “I don’t feel like doing this anymore.” In Steven Pressfield’s book The War of Art, he calls this feeling “resistance,” and it’s the feeling of reluctance or frustration that you’ll get whenever you try to do something creative and difficult. For most of us, we’ll have to push past that feeling before we can ever achieve something we can be proud of.

On the other hand, sometimes a process really isn’t working. How long should you keep at something without seeing any results, before you give up?

One answer is that you should set that limit before you get started. Hopefully this is the time during which you will be the least biased, either by wanting to give in to doubt and cutting the time too short, or by being too stubborn about sunk costs and hanging on for too long. Separate out the planning and execution phases. Planning is when you indulge and explore your doubts. During execution, you faithfully hold to the commitments you made during planning.

In some ways though, this begs the question. How do you set the limit during planning? It depends almost entirely on the situation, but here is one piece of advice that’s been useful to me: do things for just one iteration longer than a reasonable person would. The tendency is to give up too early rather than too late.

(I remember this advice attributed to Paul Graham, but I can’t find any corroboration of that.)

2

I described faithfulness earlier as a kind of corrective to the human tendency to drift and doubt. There are a few other useful hints that fall out of that framework.

When I was running a startup, I noticed that my doubts and anxieties were worst in the morning just after I woke up. We had already decided on a course of action and set a timeframe for how long we would commit to it without expecting to see any results. So this doubt and anxiety wasn’t doing me any good, it was just keeping me in bed for longer.

In a reason-based framework, I might try to stay in bed for longer while I worked out the doubts. But in the context of being faithful to my promises, I just had to remember that I had already considered those doubts during our planning and decided to commit to this course of action anyways. So I made a rule for myself: no thinking about work in the morning at all, until I had gotten on the subway. I noticed that after I had woken up a bit and started taking action, the doubts and anxieties seemed to quiet down.

A second example:

I have noticed that I tend to forget nice things quickly after they happen. At first I thought that this would just drive me to have more nice experiences, instead of resting on my laurels. But this tendency became a problem when my wife started working long shifts for her medical residency. Sometimes I would get the feeling that she never did anything nice for me at all. Did she even appreciate or value me? If she did, why was I feeling this way?

When I really focused my attention on the question, I could remember that of course we’d had many great experiences together, and that in fact she was as warm and attentive as anyone could ask when we had time together. The problem was just that we’d sometimes go weeks without more than an hour or two of real quality time together when her schedule got busy, and in the meantime I would forget all about the great times that we’d had, unless I tried really hard to draw them back into my attention.

So I started to keep a log of nice things that we’d done for each other, and I found that it was much easier to just consult that log when I was feeling down instead of trying to recall those memories unaided. This was incredibly helpful for staying faithful, not just to the narrow sense of sexual monogamy, but also to those other promises that we make: to love and to cherish, in good times and in bad. And I think the key there was just to remember that the tendency is to doubt and forget, and not to place too much stock in those feelings.

A third tip is to surround yourself with people who are trying to stay faithful to the same kinds of things as you. If your friends are all building the same mental habits as you, things go much easier than if they are cynical and doubtful about the things you’re trying to hang on to.

3

Finally, of course, it helps to have faith in the right things. I think we’ll leave that outside the scope of this post though.

Faith is not a process for choosing what to believe in or what to commit to. It is a tool for helping with what comes next. Creeping doubt and regression to status quo is natural, even in the absence of any new evidence. Faith is the virtue of counteracting that regression, through repeated internalization of those truths and commitments.

I hope you can find a few things that are worthy of your faith, and that having found them, you will be faithful.

Group Coordination at Raves

Think about the last time you tried to get eight people to do the same thing. Now imagine that four of them are on drugs, two have to use the bathroom, you’re all in a crowded arena filled with a hundred thousand (100,000) other people, and none of your cell phones work.

Welcome to group coordination at raves.

1

I exaggerated slightly. It’s far too loud to hold a phone conversation, but you can infrequently send and receive text messages. However, the network is overwhelmed by the hundred thousand other people who are also texting their friends, so your messages will be delayed by ten to thirty minutes and might fail outright.

Here are some common scenarios you might find unexpectedly difficult to solve.

You and some friends have a great view of the stage, but you can’t find the rest of your group. You’re willing to abandon your spot but only if you’re confident you can meet up with them.

You find yourself unexpectedly alone. You’re willing to do whatever it takes to find your friends, but you aren’t sure how to coordinate without reliable text service.

You are waiting for a friend at a pre-arranged meeting spot but they aren’t showing up. You were 5 minutes late for your agreed-upon time, so you aren’t sure whether they showed up and left already, or they are still on their way, or they decided not to show up at all.

A normal person in one of these situations might send a text like, “I’m near the Circuit stage, want to meet up?”

That message would be a complete failure. One of your friends might see the message 30 minutes later, and at that point they will have no idea if you are still there or even precisely when you sent the text. They could text back to confirm, but then you will face the same issues when you get their message.

Here is a better message: “Can we meet under the giant daisy at 2AM? Currently 1:15, I’m with Jess and Sam. Will wait there for 10 min.”

The important components here are a timestamp, a rendezvous time far enough in the future that your message will likely be read, and a plan that you can unilaterally commit to.

When your friend gets this message, they will have much more information to work with. If it’s past 2:10 when they see it, they will know not to bother. If they get the message in time, they can begin heading to the spot without waiting for more round-trip texts. Also, they will know how much they want to join your group. For some people, that answer will depend on who else is with you, and also on how much fun they are having at that exact moment.

2

Let’s take another look at scenario 3. You’re sitting under a large daisy sculpture, wondering if your lost friend is going to show up at all or whether you already missed them. You’re getting cold and feeling impatient to get back to the lights and music. How long should you wait there? How long should you have asked your friend to wait?

Of course the immediate answer is that you should wait as long as you committed to waiting. A surprising number of people won’t do this, and it’s always disappointing to see. But how long should you commit to waiting in the first place?

When I first started going to raves, I often committed to 10 minutes and waited for up to 20. It seemed like a classic (iterated) prisoner’s dilemma, and I’d always want to cooperate with my friends and seek the greater good of the group. I thought that people who weren’t making the effort were being selfish and short-sighted. There’s really nothing worse than being alone at one of these events if you don’t know anyone else – something about the whole experience brings out this deep need for connecting with other humans at the same time that it makes it very difficult to even stay in proximity with them.

Over the years, I’ve changed my mind on this. Different people want different things – some just want the lights and music, some want to be part of something bigger, and some have one or two friends that they really care about and are indifferent to the larger group. If you make them commit 20 minutes of their night to the cohesiveness of a group they just don’t care that much about, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment.

There are also these little perfect moments where the lights are just right, you’re feeling the beat in your chest and in your feet and in the eyes of the strangers around you and the DJ on the stage, and these fleeting moments are impossible to predict. If I knew that one of my friends was having that perfect moment, I wouldn’t want to drag them away from it. I value people who keep their commitments, but I also want to build in the flexibility to enjoy the magic when it happens.

My updated answer is that you should pick one or two buddies that you absolutely commit to sticking with. If they go to the bathroom, you go with them or else you stay rooted to the spot where they left you for an hour if you have to. For the rest of the group, set some meetup times at the beginning of the night, give it five minutes or ten at the most, and make it explicit that people can bail if they want to.

Be honest with yourself about whether anyone in the group wants to be that buddy for you. If not, you’ll have to make some compromises or be ready to go it alone. I’ve sometimes paid for friends’ tickets if they were on the fence, just to have someone reliable on hand.

3

Coordination is hard at the best of times, and breakdown is inevitable at events like these. I once took a taxi 40 minutes out into the desert at 6 AM to rescue friends who had skipped out on their planned ride back and gotten stranded at the racetrack, only to discover that they also skipped out on me. (Still love you guys!)

Everyone is out there seeking their own bliss, that elusive perfect trick of light and sound and drugs too if we’re being honest, and no two people ever want or get exactly the same night. Good intentions and promises often aren’t enough when the lasers flash, the beat drops, the roll peaks. Sometimes it’s all too enticing and it’s just too easy to get separated in the night and the massive pressing crowd.

But there are other perfect moments that I remember too, when people do follow through on their promises and come through for their friends. They miss out on their favorite DJs to take care of people who need them, wrestle themselves down from serotonin highs long enough to reunite for the one set we promised we’d do together. What makes those moments possible? Sometimes it’s the strength of friendships, sometimes it’s dumb luck. Sometimes, I think, it’s the grace and synchronicity and unity of all things, the hidden oneness that pulses underneath and alongside, always.

And sometimes, it’s because you sent the right text.